Enjoying Morning Tea

In Guangdong, at some of the older and better-known teahouses, early in the morning there is already a queue of people waiting for the doors to open. They are preparing for the most popular of Guangdong culinary customs: tan zao cha . In Cantonese, tan means “to enjoy”, zao means “early” or “morning”, and cha means “tea”, so together the phrase means “to enjoy morning tea”.

Regular customers often have a particular spot that they prefer to sit in. After they are seated, the server will give them a menu card and record the number of people in the party, then charge the tea fee based on how many people there are. They can choose from teas such as Oolong, Pu’er, chrysanthemum and Shui Hsien, and can get free refi lls as many times as they want. To add water they don’t have to call the server over, they simply put the teapot lid at an angle so that half of the opening is exposed, and the server will add water while passing by.

Enjoying morning tea is also known as “drinking morning tea” or “eating morning tea”, the former of which is easy to understand, but how do you “eat” tea? In Guangdong-style morning tea, the tea itself plays just a supporting role, the main role being the snacks, known as dim sum, so morning tea is often known simply as dim sum. A single pot of tea may be accompanied by over a dozen varieties of dim sum of all shapes, sizes and colors, held in stacks of small bamboo steamers on a cart that the server pushes around in the restaurant. Customers then stop the cart and take a look at each of the steamers, choosing whichever ones they like. There are six sizes of dim sum, namely small, medium, large, top, special, and extra special, each of which has its own price point. After the customers have chosen their dim sum the server will record their choices on their card with little stamps. To pay the bill the cashier simply adds up the different stamps. There are also dim sum that have to be ordered before they can be made, and thus do not appear on the cart. Apart from the dining area there is a group of long tables, behind which the cooks make what the customers order, then send them to the dining tables.

From the Qing Dynasty to present day, dim sum has undergone constant fusion and innovation, resulting in the creation of up to 1,000 varieties. Its origins lie in the traditional snacks enjoyed by Guangdong locals, as well as variants of gluten-based foods from northern China, and baked deserts introduced from Western countries. A typical teahouse can serve hundreds of different common snacks, but with so many choices, which ones are the true classics? Next we’ll recommend some of the musttry dim sum that you can get at Guangdong-style teahouses.

The dim sum that you must try first are of course the ones that are steamed in bamboo steamers. Steaming involves putting the stacks of steamers on top of a pot of boiling water, so that the rising steam cooks all the food inside. Other than bamboo the steamers can also be made of wood, and steaming gives the food a naturally light taste. Steamed shrimp dumplings are a worthy staple of Guangdong-style teahouses. The wrapper is made of wheat starch, and is translucent when cooked, with a fine texture. The filling is made from full, fresh shrimp and ground pork, accompanied by diced bamboo shoots or water chestnuts. The dumplings are tasty and chewy but don’t stick to your teeth. Shrimp dumplings originated at a small teahouse in a riverside town of rural Guangdong, where fishermen would often pole boats on the river peddling their catches from the day. The owner of the teahouse was inspired to buy some fresh shrimp, to which he added pork and diced bamboo shoots to make the filling for dumplings. Due to their great taste the dumplings quickly rose in popularity, and after revisions by other cooks in the town, eventually they became a dim sum specialty.

Immediately after shrimp dumplings in the dim sum hierarchy is shrimp shaomai (steamed open-top dumpling stuffed with shrimp). Shrimp shaomai are made with thin, golden-colored wheat wrapper and filled with pork, with shrimp at the top, lightly sprinkled with crab roe, for a unique and attractive appearance. The wrapper of shrimp shaomai serve as a testament to the skills of the cook, since if they are too thick they will be tough and detract from the texture, while if they are too thin they will break and ruin the appearance, so they must be somewhere in between to preserve the perfect balance between texture and look. The pork used has its own requirements; it must be a flawless combination of fresh regular and lean ground pork, so that it has just the right amounts of elasticity and juiciness, and when combined with the fresh shrimp and crab roe is extremely tasty and satisfying.

Another of the biggest sellers in dim sum is steamed “Phoenix claws with bean sauce”. Of course the “phoenix claws” are just chicken feet. But as simple as these little feet may look, they’re by no means easy to make. First they’re fried in oil, dried, steeped in cold water, and then steamed. Only through these many steps can the “phoenix claws” become so bright and taste so great, the meat having just the right crunchy texture, and sliding right off the bone. With the addition of bean sauce made from yellow or black beans and several other special ingredients, the flavor is absorbed right into the entire claw, so that many people are reluctant to put it down even after all the meat is gone.

Steamed spareribs with bean sauce is another classic. Bean sauce is a type of seasoning unique to China, and involves steeping yellow or black beans in water then steaming them and leaving them to ferment. For the pork spareribs many criteria must be considered. For example, the bones of the ribs must be slightly thicker than the heads of chopsticks, and the lean meat can’t be too thick, there must be some fat on it. The ribs are then chopped into pieces. After steaming, the meat should be light-colored and tender, easily slide off the bone, and feel thick and moist, and crunchy and chewy without being too mushy. The bean sauce then further heightens the flavor.

Char siu bao (steamed buns filled with barbecued pork) are one of the most representative staple foods found in dim sum. There is a very popular Cantonese song by the same name, which gives an idea of how much people from Guangdong like them. Char siu bao are made from pieces of barbecued pork with a specific ratio of lean meat to fat, which are cut into small pieces and flavored with oyster sauce and other seasonings to make the filling. The fluffy white buns are made from leavened dough, then made into the shape of a little bird’s nest, and steamed until the tops split open, offering a glimpse at the abundant filling made from red, juicy meat, making them extremely hard to resist.

Custard buns are a special type of Guangdong pastry. They’re large, round and puffy, and inside the white, chewy outer wrapper is the semi-liquid filling made from egg yolk, pork oil and condensed milk, for a taste somewhere between salty and sweet. Good custard buns, after being bitten into, should have filling that pours out like golden sand, taking many first-time tasters by surprise. The process for making custard buns is quite complex; first the wrapper is hand-made from dough, and must be strong enough to hold the filling while being soft when bitten into; then a considerable level of skill is required to wrap up the filling, so that the heat from the steam can fill the bun evenly, resulting in the perfect custard bun, an unforgiving test of the chef’s skills.

Of course not all dim sum are steamed, and dim sum cooks must be masters of many other culinary methods, including frying, deep-frying, braising and baking. Some of the well-known fried and deep-fried dim sum include pan fried radish cakes, fried dumplings, haam seoi gaau (salty dumplings) and deep-fried spring rolls. Pan-fried radish cakes are a favorite among locals of all ages; they’re made with fresh grated Chinese radishes, fried with diced sausage, cured meat, shrimp and shiitake mushrooms, then mixed with rice flour, and steamed into cakes. Just before they’re eaten they’re cut into thick slices and fried on either side, so that they’re crispy on the outside and soft on the inside, and hot and tasty throughout. The only way to make them better is by dipping them in XO hoisin sauce.

No dim sum meal would be complete without some sweets, the most common of which at Guangdong-style dim sum restaurants being egg tart, which is representative of Western influence in dim sum. The soft, crispy crust holding the filling made from eggs, milk and sugar for a smooth and sweet texture is the favorite of many Guangdong locals.

There’s also a unique type of dim sum called rice noodle rolls, or coeng fan in Cantonese. The wrapper is made by grinding rice into a pulp, which is placed on a special type of cloth and steamed into a thin, translucent sheet. Then a filling containing shrimp, barbecued pork or beef is spread on top, steamed and then rolled. Rice noodle sheets are as white as snow, and as thin and translucent as cicada wings, with a smooth and slightly chewy texture. As early as the late Qing Dynasty rice noodle rolls had been found sold in Guangzhou. They were so popular that supply could not meet demand, so people would often wait in line to buy them, hence the nickname chiang fan “rolls to grab for”.

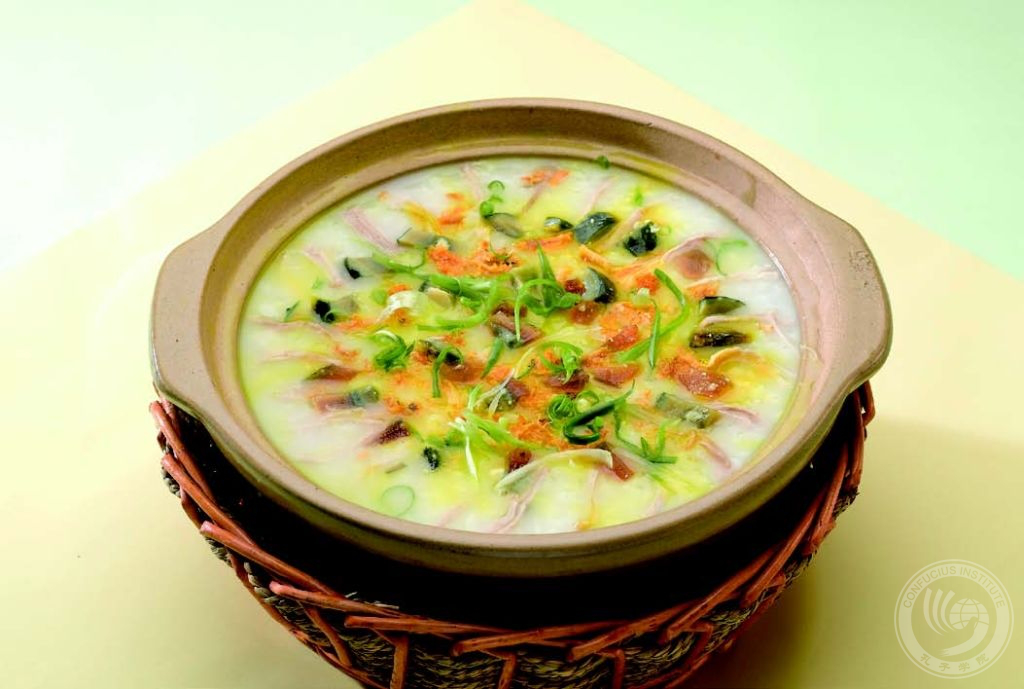

Although porridge, or congee in Cantonese, is not technically a type of dim sum, it’s an integral part of any Guangdonger’s morning tea. Making Guangdong-style congee involves a meticulous and time-consuming process. Instead of water, broth made from fish and pork bones is used. Only the choicest round-grain pearl rice harvested the same year is acceptable, which is first steeped in water, then brought to a boil over high heat, and then left to simmer over low heat for another two or three hours, being stirred all the while. This will yield a thick, smooth base for the congee, to which various ingredients can be added to create dozens of different flavors, including preserved egg and lean pork congee, tingzai “small boat” congee, shrimp and crab congee, fish congee, and so on. Just before eating the congee, crispy things like fried peanuts or pieces of dough twists can be added, for a more layered and distinctive texture.

To truly enjoy morning tea, one must take one’s time. Dim sum, to the people of Guangdong, is not simply breakfast, it’s a time to take a break from their normally busy lives and relax, and a great way to maintain relationships among friends. It is a unique part of Guangdong culture, and an essential part of the lives of the people there. If you ask a Guangdonger away from home what he or she would like to do most, they will most definitely tell you: “I want to go for dim sum!”